Analysis: The Tipperaryman's adventures as a grandee at large in South America involved everything from coca collection to debt collecting

Irish involvement in Spain's colonial empire is a largely overlooked chapter of history, but figures like George (or 'Jorge’) Ryan (1748-1805) highlight just how interconnected these worlds became. Ryan’s journey from Tipperary to South America reveals the complex forces that shaped the Spanish world and the surprising role the Irish played within it.

In September 1767, Ryan was preparing to depart Spain and cross the Atlantic for Peru. Despite the hazards of the voyage facing him, he was filled with a ‘leaving Spirit & resolution to advance’ himself ‘in the world’.

This was also a significant event for his family back in Ireland. As Ryan’s father was too ill to write, his brother-in-law, a wine merchant from Carrick-on-Suir, Co. Tipperary, Walter Woulfe, elected to offer some advice on his future as a colonial merchant. ‘I think you do right to go on your intended voyage & have great hopes … [you] will meet with suitable success’. But, he added, ‘the most essential means of your Prosperity in this world [is] to lead a Temperate, Moral & Frugal life’.

Having adopted the persona of a father-figure in his letter, Woulfe’s advice to live a ‘Christian’ life echoed the guidance given to countless young men embarking on ventures to advance themselves in the world. Even so, Woulfe’s counsel was still sound business advice, noting that Ryan’s character and trustworthiness would be key to securing ‘good Commissions & good Friends’ among merchants back in Europe.

But Ryan's career in South America did not turn out as expected, and he would find himself instead acting as a colonial administrator in ‘the bowells [sic] of Peru’. Ryan’s fortunes during this period were by no means exceptional, as a small but significant number of Irishmen were drawn to the Spanish Americas at this time on the back of wider political and economic developments. This has led historians to observe that one of the most promising fields for the study of Hispano-Irish relations is, without doubt, Latin America.

Ryan was the second son of Daniel Ryan of Inch (1714-1767), a Catholic landowner near Thurles, Co. Tipperary. In 1757, at just nine years of age, Ryan was dispatched to live with his uncle in Cadiz in the southwest of Spain, where he would ‘start learning all matters relating to business’. Cadiz was at this time home to a small yet prosperous community of Irish merchants, estimated in 1763 to number 27 traders with the third largest share in the port’s trade.

Cadiz attracted foreign merchants during the 18th century due to its monopoly on Spain’s colonial trade. This meant that any goods exported to the Americas or imported back into Spain had to pass through Cadiz first. Irish Catholics could live and work in Spain without restrictions, but participation in transatlantic trade was limited to Spaniards or naturalised foreigners after 20 years of residency.

To circumvent these restrictions, Irish merchants used Spanish strawmen to front their businesses and trade. For example, Joseph Valois (Walsh), a Waterford native, moved to Peru in 1753 and allegedly became Lima’s most prominent transatlantic merchant within a decade by using two Spanish brothers as frontmen. However, in 1764, Walsh and several other Irishmen were expelled from Peru when authorities began cracking down on illegal foreigners and their trade.

In 1761, George Ryan’s uncle passed away, and three years later, his widowed aunt remarried a Peruvian naval officer, Lt. Domingo Encalada Tello de Guzmán y Torres, who became Ryan’s step-uncle by marriage. In 1767, Encalada was appointed corregidor, or governor, of Pisco, a wealthy coastal province in Peru. This opportunity led Ryan to consider a career in colonial trade. It was in response that his brother-in-law Woulfe offered his words of advice to the young Ryan. To help guarantee success, Woulfe also contacted an Irish trading house in London, offering to take a half share in £500 worth of cargo that Ryan could sell on commission once he reached Peru.

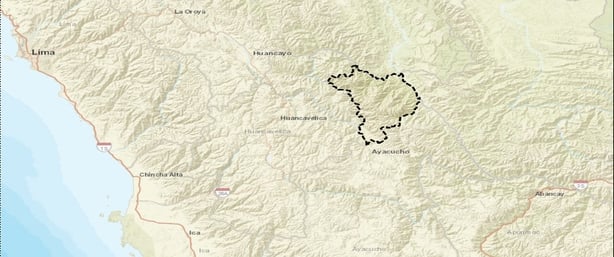

By early 1768, Ryan and Encalada had crossed the Atlantic, disembarking at Buenos Aires before travelling overland to Chile and, ultimately, Peru. They likely chose this indirect route to avoid detection by Peruvian port authorities, given Ryans illegal entry into South America. Upon their arrival in Lima, Encalada learned that his governorship had been reassigned several hundred miles inland to the remote province of Huanta. This prompted Ryan to abandon his plans as a colonial merchant and join Huanta’s militia as a sergeant major, a role that granted him legal protection from expulsion as a foreigner. With this protection, Ryan could openly assist his step-uncle’s administration.

Situated in the Peruvian Andes, Huanta was ideal for cultivating coca, a stimulant consumed by workers in the nearby mercury mines of Huancavelica. Ryan’s role involved the collection and distribution of tons of coca each year, alongside supplying mules and other goods to Huanta’s population. Where necessary, his responsibilities also extended to debt collecting, which included the intimidation of debtors and their imprisonment at times.

After Domingo Encalada's death in 1774, Ryan gravitated toward other Irish-born administrators in Peru, including brothers Juan and Patricio Savage and Hugo O’Falvey. In 1779, Ryan learned that his elder brother had died without issue, making him heir to the family’s 5,000-acre Tipperary estate. Having lost contact with his family in Ireland for over a decade, they had assumed George might be dead. It took Ryan two years to reach Ireland after 23 years abroad. His reintegration into Irish society proved challenging, with his family sometimes likening him to Don Quixote, a comparison underscoring the complexities of his return.

A longer piece about George Ryan’s exploits in Spain and colonial Peru will appear in an upcoming collection of essays on Ireland and empire.This research was funded via a Research Ireland Government of Ireland Postgraduate Research Scholarship.

Follow RTÉ Brainstorm on WhatsApp and Instagram for more stories and updates

The views expressed here are those of the author and do not represent or reflect the views of RTÉ