Speaking about his last work, his Gothic-inspired memoir All Down Darkness Wide over a recent Zoom call, Seán Hewitt said he had a clear vision for that book, one borne in his own struggles. "It sounds corny, but the sort of book I wish I could have read at the time, I found it really difficult to find anything that was honest and unafraid of kind of putting across the difficulties of either going through a depression or being alongside it."

The memoir, which won Hewitt the Rooney Prize for Literature in 2022, is a rich and devastating read, but one that is laced through with moments of joy and love, as well as endurance.

"I do also get the sense sometimes when I you know, when people are about to read it, that I kind of feel myself and go, okay, good luck. I want to kind of warn them a little bit about what's inside because I know it might be quite difficult if you're not in the best place when you start it."

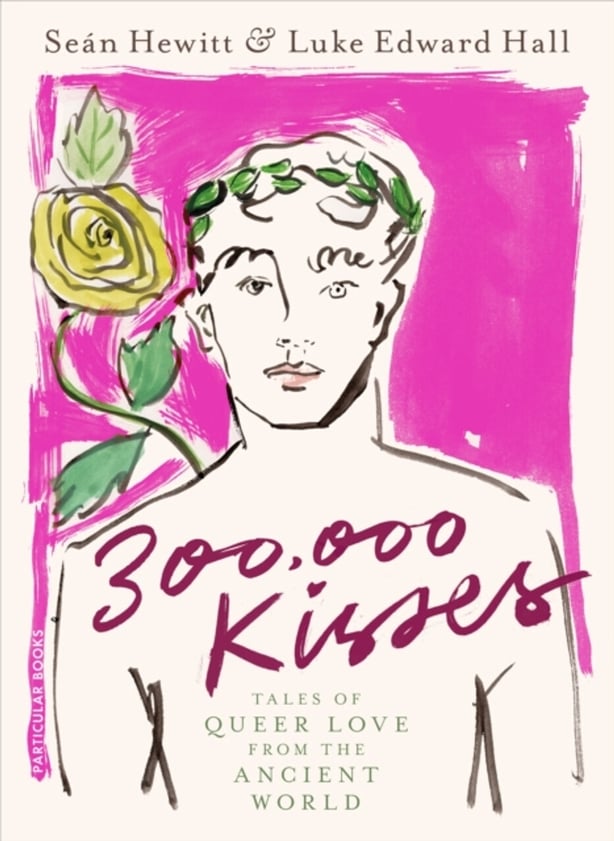

With his latest work, 300,000 Kisses: Tales of Queer Love from the Ancient World - a collaboration with illustrator Luke Edward Hall - Hewitt expands his self-made library of queer reference books. Where the memoir explored the darknesses that often haunt queer people, 300,000 Kisses illuminates a lost shared past, buffing that forgotten touchstone to a brilliant shine.

Here, he speaks about the importance of language in translation, revelling in the ordinariness of queer love and restoring queer identity and sexuality to the pinnacle of culture.

This interview has been condensed for clarity.

What did you want to create when you joined the project?

I definitely saw myself in this book as a sort of conduit, a channel for it to come out into the world. I think both Luke and I felt very strongly that a lot of people are raised with a question about their place in history or a sense of their forebears, which will give you a sense of belonging. People can often be raised with a sense of loneliness, which is kind of part of All Down Darkness Wide, which comes from feeling, I say in the prologue to the book, unmoored in history, not having a place or a literature or seeing those things as a recent development in culture.

We have queer literature from the 20th century and the 21st. It's more difficult to go back. So I very much wanted this book to be, in a way, an opportunity to give a past or a history back to people, to let them have access to it, to show a lot of variety in the way that we think about sexuality and gender. And also, we felt quite strongly that this was a book that in some way embarrassed our current level of debate on some issues such as gender identity and stuff. When you put them in the context of a 2,500-year literary and cultural tradition, it starts to sound very silly and petty and parochial.

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

Listen - 300,000 Kisses: Tales of Queer Love from the Ancient World - Sean Hewitt talks to RTÉ Arena

When it comes to translation, what did you learn about their message when viewed through the lens of what language we use and choosing the right word?

It's a really interesting question, and one that we grappled with a lot when we were writing the book. It's not so easy to use any of the language that we have for sexuality to describe sexuality. In the ancient world, there were obviously people that were attracted to people of the same sex, but whether they would see themselves as gay no, they wouldn't. That was why we went for the word "queer", as well, in the title of the book. We found that it was a bit more flexible and pliable.

One thing that we found was that some of us knew these stories before, but either the context had been taken away from the story, so we didn't know it was a queer story. I grew up near Manchester, and in Manchester Art Gallery, there's John Waterhouse's painting of Hylas and the Nymphs, which is Hylas surrounded by a load of naked women being pulled into a pond. So I thought it was a heterosexual myth. But if you zoom the camera out, you realise that it's actually in the context of his lover looking for him and they're trying to get back to each other.

They're also texts from a culture with many issues. I wanted to be clear that this is not a utopian culture. It's very misogynistic. There were enslaved people. There were disenfranchised people. But what we wanted to do was give a full range of the emotional territory of love. So anger, jealousy, quite problematic power dynamics, and let it speak for itself. So we didn't really want to be in the business of censoring it again, this material, by trying to make it conform to our own standards.

The thing that I found was just how ordinary some of these stories were. Was that deliberate?

Yeah, it was one thing that I noticed as we were going through these texts, that in some of them there was an obvious shock factor where they wanted the reader to be shocked by something and in other things it was just a remark, a sideways comment, a bit of context, part of everyday life. And it's strange that that should appear kind of revolutionarily normal, but to me it did.

The purpose of this translation was to make the text accessible, vibrant, direct and normal in some ways. And so the language I used and the forms I used were all put in service of not wanting to take you out of that moment.

I think if I could sum up what this book taught me along the way, it would probably be perspective.

The impression that I got from All Down Darkness Wide was that it was you writing your way out of an assumption you'd been taught about what it was like to be queer, that all roads lead down to something terrible. Here, there's a lot of moments of rapturous joy. Was that something that you were conscious of, that this might be a lighter shade to the experience of queer people?

It was, in some ways a reckoning with my own history, but then with societal or cultural history. And I wanted that book to end at a point of light and possibility for remaking and starting again. And it seemed that 300,000 Kisses might be a good place to kind of go back to the start, to remake something, to give a different historical beginning and to base it in colour and joy and variety.

We're often taught that the classics are kind of the pinnacle of culture. And I think if anything subversive might be achieved by this book, it is that showing queer people that they are also integral to the highest culture and that they have a place there, and that that is a culture that is very different to our own.

Did it teach you anything about what it means to be queer, or give you a different understanding of your foundation in just human experience and just being part of the broader experience?

I think if I could sum up what this book taught me along the way, it would probably be perspective. And it's given me perspective not only on things I might still be ashamed or embarrassed about, it's given me historical perspective. It's also given me a good literary perspective in terms of literary history and the place that contemporary writers taken it. In some ways it's quite good to be reminded of your smallness in the grand scheme of things.

300,000 Kisses: Tales of Queer Love from the Ancient World is published by