Analysis: The absence of Broderick's books in Ireland meant rich and complex images of gay people produced by a talented novelist were not available

By Christa de Brún, South East Technological University

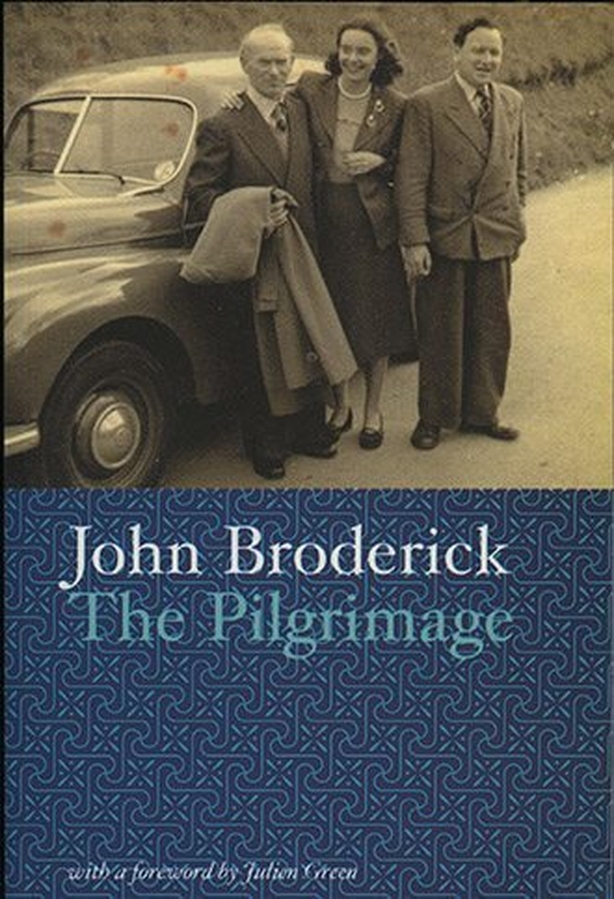

June marks Pride Month in Ireland so it's an apt time to consider the silencing of homosexual voices throughout the 20th century and the marginalisation of queer Irish writers in favour of the heteronormative values of Catholic Ireland. One of these is John Broderick. In 1961, the Athlone writer's debut novel The Pilgrimage was banned by the Irish Censorship Board under the Censorship of Publications Act because of its depiction of adultery and references to homosexuality.

Broderick was outspoken on such censorship. He referred to the censoring of the works of Liam O'Flaherty as 'a disgrace to Ireland’ and criticised the censorship of Francis Stuart and Lee Dunne, declaring of Dunne's Paddy Maguire is Dead that ‘it is criminal that people can have the power to ban such a book’. Writing about censorship in Ireland, Anthony Keating notes the concerns of the editor of the Catholic Bulletin, who observed ‘the mind of England has been trained to criticise and think for itself; that of Ireland to believe and accept what it is taught’.

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

From RTÉ Archives, Gerry Reynolds profiles author John Broderick for RTÉ News on the occasion of his death in 1989

His words were echoed by Seán Ó Faoláin, perhaps the most strident critic of the censorship laws: 'our Censorship tries to keep the mind in a state of perpetual adolescence in the midst of all the influences that must, in spite of it, pour in from the adult world’. O’Faolain himself had incurred the wrath of the Censorship Board in 1936 when his novel Bird Alone was banned. In response to this, he resolved to consistently attack the board in much the same way as Joyce declared war on the Catholic Church, considering their excessive approach a sign of nationalism in decay.

Following the prohibition of Bird Alone, Frank O'Connor, also a censored writer and the subject of the first appeal put to the Censorship board in 1946, wrote that the censorship was 'obviously not intended to protect the Irish people against evil literature, but to destroy the character and prospects of Irish writers in their own country'.

In a 1987 interview with Julia Carlson, Broderick was asked if he appealed the ban and replied ‘I don’t think you can appeal to people who are as stupid and narrow-minded as that’. Indeed, most authors refused to partake in this process, believing that to lodge an appeal would be to legitimise a system that O’Connor described as ‘an insult to Irish intelligence’. Broderick concluded ‘I didn’t think they had that moral right, so it would never occur to me to appeal’.

As well as the shame and disillusionment which affected writers on a personal level, Liam O'Flaherty, the first Irish novelist to have his work censored in Ireland, highlighted the problem of stigmatisation and the unofficial extending of censorship. A ban on one work effectively led to a boycott of subsequent publications by the same author; books were not on prominent display in bookshops or reviewed in the Irish daily newspapers, most notably The Irish Press, owned by Éamon De Valera and his family.

"There is hardly a single newspaper in Ireland that would dare print anything I write", O'Flaherty wrotein 1932. "There is hardly a bookshop in Ireland that would dare show my books in its windows. There is hardly a library that would not be suppressed for having my book on its shelves."

Broderick too speaks of ‘a certain group of people who had a considerable influence on the libraries and perhaps on the bookshops who tried through the Censorship Board to prevent people reading The Pilgrimage, in particular, and subsequently by private censorship afterwards’. In 1968, The Trial of Father Dillingham was turned down by an English publisher, which led to significant damage to Broderick’s career.

It pushed him into a self-imposed exile and this sense of displacement haunts Broderick’s later writing, as he lived out his last days in Bath, a lonely figure. As Madeline Kingston notes, ‘had this novel been accepted by a publisher in 1968, it might have given the author’s career an impetus that would have saved him the "lost" drinking years that preceded the 1973 publication of An Apology for Roses'

Notwithstanding the loss of sales and royalty income for the author, perhaps the most insidious aspect of censorship for a writer is the undermining of their relationship with the community and the erosion of their influence on the Irish cultural landscape. Although Broderick was elected to membership of the Irish Academy of Letters in 1968 and received their annual Award for Literature in 1975, he was and remains relatively obscure, despite his profound significance as a ‘chronicler of midland life’ because his books were not given the opportunity to become part of the Irish literary landscape.

The absence of Broderick's books meant that rich and complex images of gay people produced by a talented novelist were not available

The Pilgrimage marked the emergence of a queer Irish sensibility. "Had The Pilgrimage been freely available in 1961 and The Trial of Father Dillingham in 1968, they would have made a difference in Ireland", noted Colm Tóibin in 2003. "They would have filled a silence about homosexuality that was almost total. It was not merely that homosexual acts between men were illegal; they were unmentionable. The absence of Broderick’s books meant that rich and complex images of gay people produced by a talented novelist were not available. It was not as though there were other Irish authors dealing with these subjects in the 1960s."

Modern Ireland is much changed and there are now myriad voices reclaiming equality, diversity and inclusion. It is timely, then, to reclaim a space for these narratives in the public sphere as an integral part of the social fabric of Irish culture, and to create a space for his perspective to inhabit and inform our cultural landscape.

Follow RTÉ Brainstorm on WhatsApp and Instagram for more stories and updates

Dr Christa de Brún is a Lecturer in English Literature and First Year English Co-ordinator at the South East Technological University (SETU)

The views expressed here are those of the author and do not represent or reflect the views of RTÉ