Dr. Páraic Kerrigan's Reeling in the Queers contends that while the 'big stories' of the decriminalisation of homosexuality and Marriage Equality have been told to name but a few, between these events lie intricate threads of ordinary people, with extraordinary stories to tell.

This book aims to look beyond the grand events and between the cracks and fissures of these big moments, to tell the lesser-told tales of Ireland's LGBTQ community.

The book comprises 14 stories/vignettes, among which include Hollywood superstar Rock Hudson's weekend on the Irish gay scene, censorship of LGBT children's literature in the 1980s, Phil Moore, the mother of a gay son who led gay law reform, the world's first gay boyband (which was Irish!) the AIDS priest and his ministry and the plight of a lesbian mother trying to maintain custody of her children.

While many in Ireland’s LGBTQ community may not have changed laws, their actions provided hope, relief, support and, crucially, created enclaves of fun and queer joy. This book aims to reel in the stories of LGBTQ individuals, events and figures: stories that have left an indelible mark not just on the queer community but on modern-day Ireland; stories that bear witness to the resilience of queer culture, a testament to how it emerged and thrived against all odds, and the people who made it happen.

Below is a short extract from Chapter 6: Pink Carnations and Pink Triangles: The Emergence of Pride in Ireland (1974–1982).

In the early 1970s, the efforts to commemorate the Stonewall Riots quickly became a transnational movement through Pride, which took a variety of forms, from parades to parties and protests to proms. The globality of Pride, particularly as a form of protest, can be seen from collaborative activists' efforts, especially in Europe, one of which resulted in Ireland’s very first Pride demonstration.

In June 1974, the Norwegian gay organisation Det Norske Forbundet announced that their Pride celebration for that year (Gay Liberation Day) would be dedicated to highlighting the criminal laws around homosexuality in Ireland and the climate of homophobia engendered by the Catholic Church.

The protest took the form of a demonstration outside Oslo’s British embassy, with placards declaring 'Stop the oppression of Irish homosexuals’.

Encouraged by their Norwegian counterparts, Irish gay and lesbian activists arranged the first-ever Pride demonstration on 27 June 1974, where they similarly picketed outside of the British embassy in Dublin and then marched on to the Department of Justice with placards stating ‘Homosexuals are revolting’.

David Norris, one of the activists present at the first Gay Pride march, recalls how many on the streets of Dublin were horrified to see such an overt and public declaration of homosexuality. He recounts that the 46A bus nearly crashed into the railings of St Stephen’s Green, so shocked was the bus driver.

Another incident involved a lorry that had just been parked outside the department to deliver a new carpet for the Minister for Justice’s office. As Norris recalls, ‘One man got off the lorry and said, "Jaysus Mick, fu**ing queers!" Mick got out, took one look at us and said, "What about it? I don’t give a bo***cks, a picket is a fu**ing picket." He took up my placard and walked around with us for five minutes.’

While Ireland’s first Pride march and demonstration was a small affair, involving only twelve activists, the Pride 1974 event demonstrated the power of Pride as a protest, a means of creating solidarity with allies and a vehicle through which public visibility could be achieved.

While Pride continued to grow into an annual, broader international movement, its development stalled in Ireland from the mid to late 1970s. This was mainly because a small number of activists within the broader Irish gay civil rights movement were focusing on establishing solid physical and social infrastructures for the movement. The first flush of activism evident with the founding of groups such as the Irish Gay Rights Movement (IGRM) in 1974 saw these organisations channel energy into developing social and cultural outlets for the community, with a focus on finding physical spaces.

Alongside this, the late 1970s saw a concerted effort around campaigning for the decriminalisation of homosexuality, with David Norris, Bernard Keogh and Edmund Lynch founding the Campaign for Homosexual Law Reform in 1977. Notwithstanding this flurry of politicisation, a couple of these early groups imploded and fell apart.

It would be five years before Pride would reemerge, in 1979, with the founding of a new organisation, the National Gay Federation (NGF). The NGF brought with it a fresh political and social structure, along with a more permanent physical space in the form of the Hirschfeld Centre, which provided the human and economic resources to realise a full Pride programme once again.

Ireland’s first Gay Pride Week was organised for the final week of June 1979, with the NGF determined to ensure that the Stonewall Riots were commemorated.

(Source: NLGF Collection, IQA/NLI)

Courtesy of the National Library of Ireland

Gay Pride Week 1979 provided a suite of social, cultural and political activities, which demonstrated a growing movement and confidence within Irish gay civil rights activism. In terms of a political consciousness, a forum was held at the Hirschfeld Centre with members of Ireland’s prominent political parties, including Michael Keating of Fine Gael, Niall Andrews of Fianna Fáil, Ruairi Quinn of the Labour Party and Noël Browne.

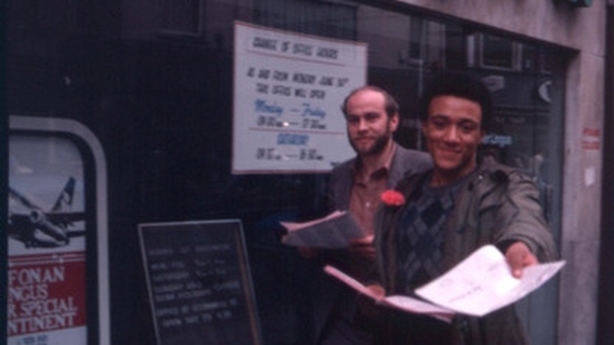

Political activities also took place on the streets, where a leafleting campaign was organised at the top of Grafton Street, engaging the public, asking them to support ‘our campaign for legal and social change and explaining our views of life and what we see as our rights’.13 In terms of cultural activities, Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s movie about a gay man in West Germany who wins the lotto, Fox and His Friends (1975), was shown in the Hirschfeld’s film theatre, the Hirschfeld Biograph, demonstrating an engagement with queer cultural production.

The Gay Pride Day event, which took place on the Sunday, was demarcated for a Pride Picnic, a tradition that would build and continue throughout the early 1980s. The picnic took place in the Hollow in the Phoenix Park, where attendees were told to ‘bring along a musical instrument and wear a Gay Pride Week badge’.

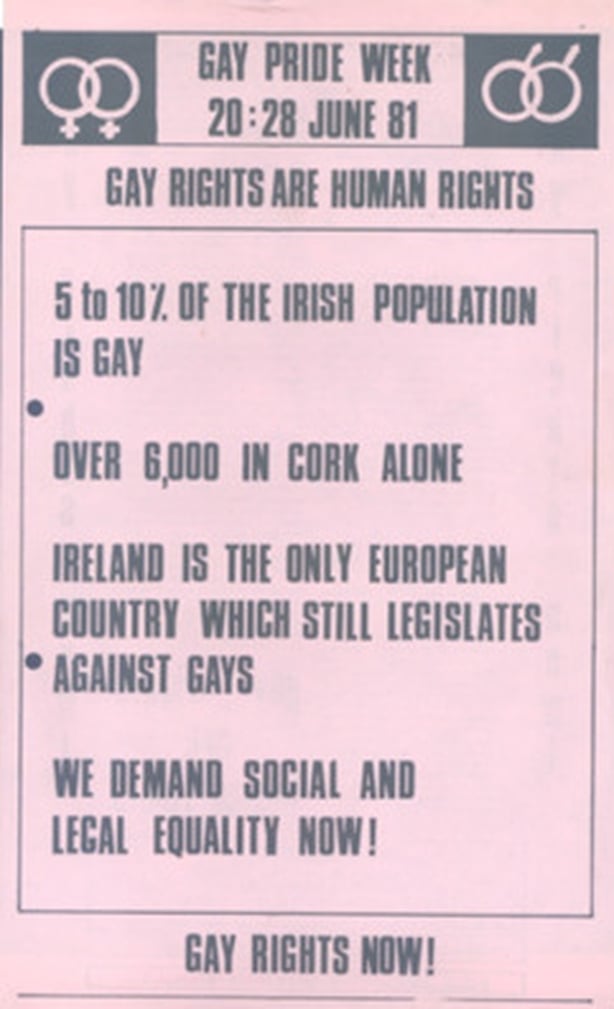

The successful week of events started the momentum for a more consistent slate of events for Pride Week, coalescing simultaneously around a community growing in confidence and visibility and becoming more coherent in their political, social and cultural activities. Gay Pride Week 1980 took place once again at the end of June, with the goal of reassuring gay and lesbian people that there was a community for them if they wished to join.

(Source: Kieran Rose Personal Archive)

Courtesy of Kieran Rose

Pride also continued to demonstrate to isolated LGBTQ people an awareness of shared existences and desires. The information leaflets developed by the NGF for Gay Pride 1980 explicitly connected the ideas of Pride with the Stonewall Riots, providing a brief history of the latter and how they generated a global Pride movement.

Tonie Walsh, one of the core organisers of Gay Pride 1980, noted how the distribution of leaflets and pink carnations was one of the cornerstones of Pride, enabling the community to directly engage with the Irish public. He recalls early on the Saturday morning of Gay Pride Week going down to the Smithfield flower market and buying boxes upon boxes of pink carnations to hand out alongside the information leaflets.

The pink carnation was a reference to gay Irish man and playwright Oscar Wilde, who in 1892 ‘instructed a handful of his friends to wear [green carnations] on their lapels to the opening night of his comedy Lady Windermere’s Fan.

The green carnation became a subtle, subversive code around gay desire. Walsh notes that dyeing the many pink carnations green would just not have been possible at the scale necessary, but at the very least, using the carnations harnessed the cultural symbol of Wilde, venerating it through a Pride event.

Many members of the public were amused by young gay men and women walking around the streets, offering them pink carnations, and accepted leaflets about riots in New York they had never heard of. The leaflets stated: ‘Stonewall is now eleven years past. The main assertions have been made, the necessity of being visible, to come out and let other people know you are gay. The other assertion was the need for community to come out together, to gain strength by everyone working together.’

Three calls for change were made within the leaflet: ‘The right to form loving relationships without being labelled criminals, the right to live as citizens equal before the law and demand for education which suits our needs.’

(Source: Christopher Robson Photographic Collection, NLI)

Courtesy of the National Library of Ireland

For the most part, as Walsh recalls, the Irish public were good-natured about the traffic-stopping on the streets, accepting the pink carnations and putting them in their lapels. One Christian fundamentalist who was preaching beside St Stephen’s Green took issue with the group and refused to take a carnation Robert Stephenson offered to him, denouncing the gay and lesbian community from his microphone. Eamon Somers, who was amongst the leaflet distributors that day, recalls initially feeling nervous, but found being visible on the streets, handing out this information, liberating.

The gay picnic was the culmination of the Pride Week once again, this year involving the release of two thousand pink balloons from St Stephen’s Green. The picnic was especially important because, while it was primarily a social event, it also involved the reclaiming of a public realm that was traditionally hostile and unwelcoming. The picnic was organised to be convivial, public and visible, without inviting the glare of homophobia or potential violent attacks.

Reeling in the Queers: Tales of Ireland's LGBTQ Past by Páraic Kerrigan is on sale now.