Debbie. Charley. Ophelia … Éowyn. Storm nomenclature means that some severe weather events seem to register a little easier in our brains than others.

Maybe that's because what were considered once-in-a-generation occurrences have become much more frequent. But there's no doubting that the impact of the battering the country took last week will live a lot longer in the memory than November's Storm Bert, or Storm Barra in 2021.

Already, Éowyn can take its place alongside 1961's Hurricane Debbie, 2017’s Storm Ophelia and another great historical weather bomb, known simply as the Night of the Big Wind.

The latter event, in January 1839, became a reference point for much more than the damage and devastation it caused. It was passed down through the generations as a touchstone date on which births, marriages and deaths took place. A yardstick in pre-digital times, to which important life events could attach.

We might have more nuanced ways of recording things now but recollections of the scale of the damage wrought by those record breaking winds last Friday week will endure, long after the clean-up and restoration work is completed.

John McDonagh, from Gleann Uisce in Co Galway reminisced this week about how his father used to talk about Hurricane Debbie, in the 1960s.

"I was talking to my cousin the other day, who also remembered it. But that only lasted an hour-and-a-half, seemingly. This lasted from 1.40am until about 10.30am. Full force. Hurricane winds. It was frightening, to be quite honest with you.

"I didn't sleep at all that night because I thought the house was going to be gone in the morning. It was terrifying."

While his home was left standing, John's sister, Maureen Folan, didn’t fare as well. She returned to her dwelling in Carna on Friday 17 January, having spent the night in her son’s house.

Images of the destruction that greeted her have circulated widely since then. The roof was ripped clean off, leaving the property uninhabitable.

"The house is 120 years old and there was a new roof put on it 15 years ago. Before that, the tin roof never moved in all that time. But then again, we never had anything as disastrous as this … people older than me say they’ve never known anything like it."

Despite the huge level of damage, there's also a sense of relief that the human toll was not greater.

Mr McDonagh says that if any cars or pedestrians had been passing through the worst-hit areas during the height of the storm, lives would have been lost. "Thankfully, on that night, there was nobody out," he says.

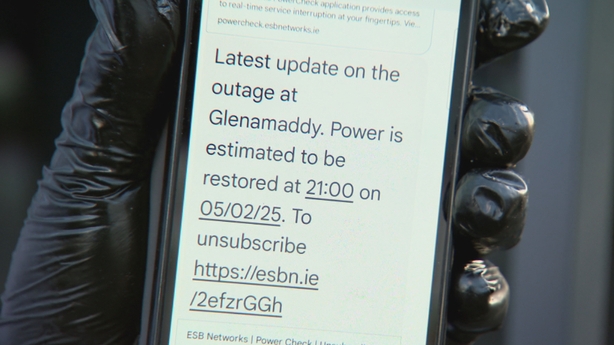

A week later, people across Conamara are still trying to deal with the aftermath. Some areas are still without electricity and there are wider issues when it comes to basic communications infrastructure, with many phone services still down, or patchy at best.

"There's no way of contacting a doctor, we're an hour-and-a-half from the hospital and the phone system is in a mess," says Mr McDonagh. He attributes much of the difficulty to a protracted lack of investment.

"There's wires everywhere, thrown on the road, there isn't a straight pole anywhere, it's really bad in the last few years and it doesn't seem to be improving."

Given the extent of the disruption and the upset it brought, the psychological impact on those most seriously affected will also remain.

"We're not cross with the workers, I suppose we're cross with the system"

Ann Flanagan from Williamstown in north Galway was one of hundreds of people who made the journey to a makeshift food kitchen in Dunmore this week. There, a charcoal barbecue was the only way for locals without the option of gas cookers to secure a hot meal.

After she collected some containers of chicken stir fry, she outlined how initial acceptance after the storm gave way to a sense of despair, as the days passed.

"I think we have been getting more emotionally flat every day and we're also getting tired. I live on a farm with my husband and my son and the difficulties are just getting worse," she said.

"We’ve had no electricity, no heat, no water for part of the time and it will be weeks before we get internet connections again. There are numerous poles and cables down.

"It was kind of exciting I suppose last Friday but then the reality dawned that we didn't have any services. I think, here in the west of Ireland, in a first world country, to be without regular household amenities, is extremely frustrating.

"We're not cross with the workers, I suppose we're cross with the system," she says.

That sentiment is shared by many.

There's a general acceptance that ESB Networks crews are stretched to the limit and the scale of the task facing repair workers is vast.

"We can't keep going like this, the whole thing is a joke"

But that's balanced by a perceived disconnect between service providers and the communities they serve.

Countless people across the areas experiencing difficulties have been wondering aloud this week how they are supposed to check online for updates on the restoration process, or call dedicated State helplines, when they continue to have no internet, electricity or telephone connectivity.

In turn, that feeds into a sense of priority being given to certain parts, to the detriment of others.

Restauranteur Ray O'Connor runs the Stone House in Ballinlough, Co Roscommon. He estimates he lost €10,000 worth of stock as a result of the electrical disruption. And that's before he considers cancelled bookings and ongoing uncertainty.

"We can't keep going like this, the whole thing is a joke. If you have to fork out and buy a generator you're talking about €20,000, where's that going to come from?" he wonders.

In many cases, the difficulties have led to displays of resilience and ingenuity.

Giovanni Moscalu lost most of his stock at Martino's take-away after the lights went out. He spent the following days trying to source a generator that would allow him to open again.

Ultimately that entailed a seven-hour round trip to Co Carlow, to hire a unit suitable to power his fryers and fridges.

Hours after he sparked it up, power was briefly restored in Dunmore. But his efforts weren’t in vain. Soon afterwards, the town went dark again.

At the time of writing, Dunmore is still waiting for a full resumption of supply.

Shopkeeper Peter Walkin says the problems were compounded by a lack of information and shifting timelines. Instead of serving customers he spent recent days sorting through perishables and frozen goods, throwing them out and filling wheelie bin after wheelie bin.

"It's hugely frustrating. We cannot plan. Our suppliers are ready to go and restock us. Locals are knocking on the door looking for bread and milk but we can't give it to them. We're in here on a daily basis just emptying shelves into the bin."

The events of the last eight or nine days have placed the focus on the country's ability to withstand the challenges posed by Storm Éowyn.

A report for the Irish Fiscal Advisory Council last October, titled "Ireland's Infrastructure Demands", identified deficits in several areas, including electricity and water.

It said that while progress had been made in recent years, more needed to be done to catch up to where we should be.

The Taoiseach said yesterday that investment in the grid would be accelerated to make it more resilient.

Prof Jamie Goggins, from the University of Galway, is the Director of Construct Innovate, which examines ways to develop sustainable approaches to the built environment.

He acknowledges the progress made in recent decades but says there are huge challenges ahead and huge investment is still needed.

"If the population is going to continue to grow then we need to be able to plan forward to provide housing, with water, broadband, electricity … all that infrastructure, taking in existing and projected demands.

"And that has to be more resilient to the various crises that are happening, be they climate, financial, wars or conflicts around the world. We need to ensure our built environment can withstand those, can adapt to them and can quickly recover when the stress is on it.

"We have to improve transport, water, energy systems, all in a way that, when it's up and running, it's resilient and not having a negative impact on the environment. We have to think about the materials we use, how we build the infrastructure and how we employ new technologies," he says.

That will require new approaches, changed priorities and fresh thinking.

Professor Goggins says it is possible, but Government policies need to make it more achievable.

At the end of a week where tens of thousands of people are still without basic facilities, those goals are of a little less importance for many right now.

Instead, a return to what they had in place ten days ago remains the most pressing need.

And while Éowyn may not trip off the tongue as easily as some of the named storms that preceded it, its ferocity is burned forever into the minds of all those whose lives continue to be disrupted by its power.